On Wednesday 23 September, the programme Cogadh ar Mhná (The War on Women) is being screened on TG4. In consultation with the documentary’s director Ciara Hyland, who interviewed me for the programme, I have decided to create a blog from a section of my published work Renegades published in 2010. This was the first time this issue was addressed within Irish Historiography and is largely reproduced in this blog from the chapter titled ‘The War on women’.

Reports of violence against women.

Until 2010 one aspect missing from the historiography of the War of Independence is the issue of ‘the war on women’ in the form of physical and sexual abuse by both sides. This was not addressed or discussed within a historical context, perhaps because public discussion of sexual assault and rape in war is a relatively modern phenomenon and the #metoo movement gave it impetus.

While being careful not to place the context of the modern world onto the period 1919-1923, it is necessary to record that women and their families suffered a terror that was not confined to armed conflict. Caught between the violence of the reprisals perpetuated by the Irish Republican Army and the Black and Tans, the lives of women within the general population descended into a living nightmare.

The period of the reign of terror by the Black and Tans in Ireland is well recorded. J.J. Lee, in Ireland 1912–1985, stated that ‘the new recruits were too few to impose a real reign of terror but numerous enough to commit sufficient atrocities to provoke nationalist opinion in Ireland and America, and to outrage British liberal opinion’.1J. J. Lee Ireland 1912–1985 p. 43 The extensive historiography of this period maintains that the Black and Tans did not assault women physically or sexually. This apparently has its origins in a statement made by Sir Hamar Greenwood, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, who in February 1921, made a statement on the issue the House of Commons. He was responding to Eamon de Valera who accused the British military and the police of outrages against Irish women. Sir Hamar Greenwood said:

In 1921 the American Commission on Conditions in Ireland3Conditions in Ireland Interim report (American Commission on Conditions in Ireland, New York, 1921). published its report and apparently took its lead on the subject from Sir Hamar Greenwood. This commission sat in New York to collect evidence from witnesses about conditions in Ireland. However, on the ground in Ireland it was perceived as a biased and pro-Republican commission and was subsequently boycotted by a significant section of the population, and it presented a one-sided perspective on conditions in Ireland.

Interim Report – The American Commission on Conditions in Ireland

The American commission stated that while it received evidence about women and girls being searched, their bedrooms entered by force in the middle of the night and accounts of them having their hair cut off, it did not receive any statement or charge of rape against the imperial troops. It recorded in line with Hamer Greenwood that:

Meanwhile there was another commission simultaneously examining conditions in Ireland, This was the British Labour Party Commission to Ireland set up in November 1920 in the wake of the party’s failure to make the British government accept responsibility for the continuing warfare in Ireland. When the party instigated the commission it had a double remit, (1) to condemn British government policy in Ireland, and, (2) examine the use of violence (‘reprisals’) directed towards the civilian population by British forces in Ireland.5Report of the Labour Commission to Ireland (Labour Party, London, 1921), p 58 In their report, the commission used the word ‘reprisal’ when referring to all acts of violence against the civilian population. This commission published its findings in the Report of the Labour Commission to Ireland and it addressed all aspects of terror and violence, in particular, the physical and sexual abuse of women by both sides in the conflict.

Report of The Labour Commission to Ireland

Report of The Labour Commission to Ireland

The British Labour delegation was given permission to read the reports of the Royal Irish Constabulary and the statements made by women who found the courage to report the violence perpetuated against them. Interestingly, this specific information is copied in the papers of Oscar Traynor, Richard Willis, John Bolster and Fintan Murphy, all of whom were senior officers of the IRA, it is unclear if they had access to these police reports at that time. This material is held in the Contemporaneous Documents of the Bureau of Military History, Irish Military Archives.

Hannah Sheehy Skeffington made a statement to the American Commission and this was then published in pamphlet form around 1921-22 by the ‘Office of the Irish Diplomatic Mission in Washington. D.C.’6Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, Statement of Atrocities against Women, to the American Commission, (published by Office of the Irish Diplomatic Mission in Washington. D.C.), 1921-22. The sources she used were taken from various newspapers like the Daily News, the Manchester Guardian and the Herald. She also used sources gathered by the members of Irish Women’s Franchise League and from her own personal experiences or observations. 7Ibid

In June 1921, Margaret Connory who was a member of the IWFL, investigated this issue in the south and west of Ireland on behalf of the Irish White Cross Committee. Her reports were published in the English-based newspaper Irish Exile in April and July 1921 under the title ‘Outrages on Irish women’.8Irish Exile, April 1921 Apparently Connory spent twenty-nine days conducting oral interviews in Cork city and the outlying districts of Macroom, Mallow and Bantry; she also visited Dungarvan in Waterford, Tralee, Ballymacelligott in Kerry, Ennis in Clare and Limerick city. She wrote of many cases of women and small children being put out of their homes, generally in the middle of the night, clad only in their nightclothes. More serious, is her description of the experiences of women who were raped and sexually assaulted. Most raids by the Black and Tans took place after the official curfew and she recorded that within the general population:

Margaret Connory believed this was widespread throughout the country. However, most of the women she talked to about their experiences shrank from allowing their stories to be told publicly.

Terror

The Labour Commission to recorded its revulsion at the level of violence perpetuated by the crown forces, and said that:

The commission examined the specific issue of violence against women but found that, in general, getting information was problematic because women were reluctant to report it, the report states that:

Lady Augusta Gregory echoed this opinion in her diaries, where she recorded that within the general population and in particular in rural areas, women had ceased walking on the roads ‘because the Black and Tans were out for drink and women’.12Daniel J Murphy, The Journals of Lady Gregory, books 1–29, pp 196–7 In isolated parts of the country, young girls and women had no protection whatsoever.

The Labour Commission delegation observed that assaults on women were constant and reported one incident to highlight the casual manner in which the Black and Tans inflicted terror. A group of Black and Tans raided a house, and entered the bedroom of a young girl, they made her get out of bed and in the resulting struggle her nightdress was ripped open from top to bottom. The report went on to say that:

This incident was also recorded in more graphic detail by Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, who recorded that:

Sheehy Skeffington also reported acts of terror inflicted on the elite republican women, saying:

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington addressed the everyday assaults inflicted on women by the military, she cited:

Lady Gregory who lived in Gort Co. Galway recorded in her diary related that her doctor, Dr Foley, told her that across Clare and Galway young girls were violated by Black and Tans but, afraid of publicity, the families kept quiet to protect their wives and daughters from scandal.

The Labour Commission delegation recorded several accounts of terror inflicted on families of lesser-known men. For example, Mary Kelly from Enniscorthy in Wexford, reported that her brother ‘was on the run’ and that the military raided on her home. Her brother ran and was pursued by ‘about twelve of the military’ They returned two hours later without him, and Mary said that a member of the party who seemed to be in command, shouted to her:

See this man caught her roughly by the hair and told her to name the man who had escaped through the window, when she refused he struck her ‘a heavy blow across the face, caught her by the hair, forced her down on her knees and told her ‘to prepare to die’. He placed the revolver to her breast and hit her a hard blow on the face and she ‘fell stunned’, when she recovered, she went outside to the yard where the men were ill-treating her father and were in the process of taking him out into a field. She said:

In another case, the commission investigated the burning of a farm. They visited the farmstead and found the farmhouse and outhouses (except for a small fowl-house) in ruins. The tenant farmer was a seventy-two-year old woman whose son was on the run. She lived at the farm with two daughters and an eight-year-old boy. The members of the commission discovered the latter living in the fowl-house. The two daughters told the commission that two police officers and several men in plain clothes had come to the farm and enquired as to the whereabouts of their brother. They ordered the women and child to clear out. The sisters and the old lady left the house partially dressed and without boots, while the ‘men poured petrol on the furniture, the outhouses, pigsty and on the pigs and poultry’19Ibid The buildings were burned to the ground and about forty of the fowl were burned to death, but the women managed to save the pigs. The family spent the night in a field and subsequently, were reduced to living in the fowl-house, while the old lady was sent to the workhouse.20Report of the Labour Commission to Ireland, p 19

Illegitimacy

Joost Augusteijn, while researching From Public Defiance to Guerrilla Warfare interviewed individuals (who remain anonymous) who told him that the usual rituals of courting were transcended, and ‘that there were some unconfirmed reports of illegitimate children being born’.21Joost Augusteijn, From Public Defiance to Guerrilla Warfare (Irish Academic Press, Dublin, 1996), p 144 John Healy in his memoir Nineteen Acres recounted that his maternal uncle who was a part of an IRA Unit in Galway was responsible for two pregnancies in that county while he was with an ASU unit.22Joost Augusteijn, From Public Defiance to Guerrilla Warfare (Irish Academic Press, Dublin, 1996), p 144 Constance de Markievicz in a letter to her sister wrote, ‘people got married on the run and many babies were born, whose fathers were on the run’.23Esther Roper, Prison letters of Countess Markievicz (Longmans Green, London, 1934), p 266

An unmarried woman or girl in a small rural area would not openly have a full sexual relationship. Pregnancy would have meant a social death, so it would have to remain secret. To be unmarried and pregnant meant social ostracism, and if an unmarried member of Cumann na mBan became pregnant, she would have been drummed out of the organisation. If the putative father refused to marry her, she had only two options: she could give birth in the local workhouse; or, if she could raise the money, move away and give birth in secret, many travelled to England. Every young female understood the consequence of sex before marriage, and there was no sympathy for the unmarried mother.

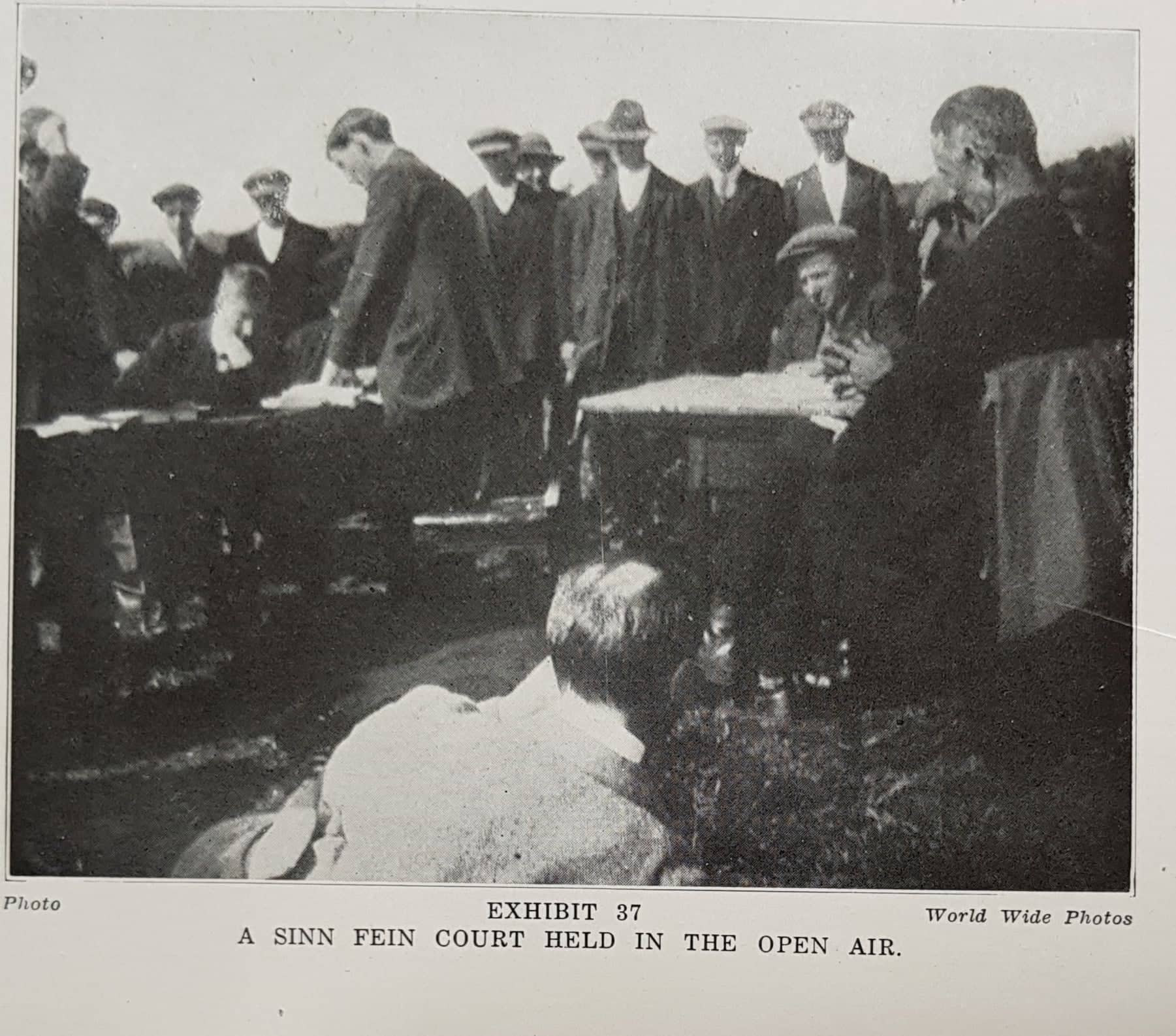

A Sinn Fein court held in the open air

An interesting case surfaced in Westmeath where a young woman brought a case to a Sinn Fein republican court against a member of the IRA named, whom she claimed seduced her and made her pregnant. Subsequently the IRA member was ordered by the court to pay the young woman ‘£200 and failing this, a grant of 30/- per week was to be paid for the maintenance of the child’. 24Esther Roper, Prison letters of Countess Markievicz (Longmans Green, London, 1934), p 266

In 1921, as the warfare descended into tit-for-tat reprisals, the population was helpless, as the terror continued, women and children were sucked into the mayhem and reduced to abject terror. The most common form of assault on women and girls was the shaving or cutting of their hair, and this usually was carried out using some form of physical violence. Both sides indulged in this practice for the pettiest of reasons, and it grew more common as reprisal became the norm of warfare used most often against females within the civilian population.

There is an interesting account in the Bureau of Military Statement on the issue from Margaret Brodrick Nicholson a member of Cumann na mBan in Galway. She worked with the men on the local ASU and her job was to relieve British soldiers of their arms and ammunition. She accomplished this ‘enticing ‘British soldiers down to the docks’, she was identified and a Black and Tan patrol arrived at her home and asked for her specifically by name. She recalled:

Nicholson states that on the following day she went to a barber to have her head shaved so that her hair would grow back properly. She also recorded in her statement that there was a public house in Eyre Square, that was frequented by Black and Tans and the girls who mixed with them ‘were warned by the local Volunteers about publicly associating themselves with the RIC and the Tans’. However, she added, ‘nothing was done to molest these girls, but their whole families cleared out around the period of the Truce and were never heard of again’.26Ibid

Meanwhile, the republican aggression on the Royal Irish Constabulary was extended towards police families. The Labour Commission delegation did emphasise, however, ‘that in the overall terrorisation of the population this was not carried out on a scale comparable with the terrorisation of the mass of the Irish people’, and that ‘the policy of this particular victimisation was regrettable because it tended to embitter the relations between the constabulary and the Irish people’.27Report of the Labour Commission to Ireland, p 80

This was no comfort to the mothers, wives, children, siblings and girlfriends of the RIC men. The domestic servants employed in RIC barracks also bore the brunt of the violence. As the RIC barracks were continuously attacked and burnt out, the families of RIC sergeants were in many cases made homeless, and citizens were afraid to help the women and children because they feared being burned out themselves. This fear was realistic. A policeman’s widow who was planning to take a sergeant’s wife into her home as a lodger, was warned by an anonymous letter not to take ‘this woman into her house’, and if she ignored the warning her house would be burned and she would be shot.28Ibid The commission told the story of a police sergeant’s wife who was reduced to living in a wooden outhouse after her home had been destroyed. The report said:

A vacated barracks occupied by another RIC sergeant was invaded by fourteen men who marched him out of the building and forced him to face a wall while they removed his four children to a neighbouring house. He protested that his daughter had influenza, but the raiders told him that she ‘must be removed as these were times when many were suffering’.30Ibid The barracks was then set alight.

One constable’s wife was visited by fifty men with blackened faces, who were carrying rifles and shotguns. They ordered her and her six children out of their house and marched them to a nearby house where the householder was ordered to keep them for the night. The masked men returned to the constable’s house burned it destroying everything. The wife of another constable reported that about twenty armed men entered her home, ‘seized her and her four children who were under six years of age and put them out on the road. Their furniture was then put outside. It was raining heavily and the mother sought refuge at the local post office, but the raiders told her that she would not be allowed to remain in the parish another night, so she ‘cycled in the rain in a deplorable condition, to where her husband was stationed’.31Ibid, p81

The girlfriends and acquaintances of RIC and DMP men were also targeted. In Dublin, a Miss Price received two threatening letters telling her that that if she continued to keep company with an RIC constable she would be punished. Another young woman reported that about twenty men forced their way into her home, grabbed her, knocked her down and ‘cut off her hair with tailor’s scissors’. The raiders then proceeded to another house nearby where another young woman had her hair cut off and was warned ‘not to have anything any more to do with the police’.32Ibid.; Oscar Traynor Collection (MA, CD 120/1/4) On another occasion, two sisters were visited by a group of armed men at night time, taken outside in their night clothes and were marched some distance away where they were court-martialled for ‘walking with the Peelers’.33Ibid They were found guilty and sentenced ‘to be shot, but this was mitigated and their hair cut off instead’. The reason given for this outrage was that ‘these girls were friendly towards the police’.34Report of the Labour Commission to Ireland, p 80

Barrack servants had a particularly hard time. In July 1921, a woman who had already been injured in the conflict, received an anonymous letter warning her that if she continued working for the police, the IRA would take steps to have her removed from the locality. In another instance, seven or eight masked men invaded the home of a barrack servant, dragged her outside and cut off her hair. They did this because she ignored a warning, she had been given to leave police employment. Another servant was removed from her lodgings by armed and masked men, who gagged her and then took her to a field where they cut off her hair, while simultaneously kicking her all over her body. Her crime was that she had taken the job of another woman who had left the job, due to the boycott of the police. On 7 August 1920, four men entered the home of another woman and seized her by the hands and feet, while another put his hands over her mouth. They then put ‘three pig rings into her buttocks with pincers’.35Ibid. p 81 Her crime was that she supplied goods to the police.

The IRA also committed crimes against women within the general civilian population. On 20 September 1921, two men held up a woman at Mountain View Road in Ranelagh, accused her of ‘having expressed anti-Sinn Féin sentiments’ and then ‘cut off her hair’.36DMP reports, Oscar Traynor Collection, Bureau of Military History CD 120/1–4 It was not just republican men who were involved. There is one report where a raiding party included women. On 2 October 1920, two women and three men entered the home of a couple named Bowes at Cadogan Road in Dublin and while one of the men held a revolver on the husband, one of the women cut off Mrs Bowes’ hair. There was no reason given for this assault. Members of Cumann an mBan were involved in these incidents

In April 1921 in Kenmare Co. Kerry a young woman was dragged from her aunt’s house by a large group of men and women and she was marched through the streets in a torchlight procession before having her hair cut off. Shots were fired in her direction, but she was not hit. She was discovered by the police in a dazed condition and required medical treatment. Her crime was that on the preceding night there was a party of police on duty in the village and she was apparently observed exchanging ‘a few words with the constables’. 37The terror in Ireland, 1919–1921 (pamphlet, NLI Ir 94109), p 34

Women suspected of being spies were also dealt with in the various IRA brigade areas. Some of the brigade areas made their own rules, and consequently treatment of women varied across the country. In Cork, on 9 November 1920, the adjutant general of the Cork No 2 Brigade issued a directive on the subject of ‘women spies’:38Richard Willis & John Bolster (BMH contemporaneous documents, CD 240/1/1)

Following this, a formal public statement was made in the form of a poster or leaflet warning women that if they were caught spying ‘they would be neutralised’.39Ibid

In July 1921, the Irish Exile published an article on the abuse of women in Ireland. This report said that the home of a married couple in Cork was invaded by two men in uniform and wearing masks. The husband, in his statement to the police, said the men had English accents, were in police uniforms, with white linen cloth masks across their faces. His wife was in an advanced state of pregnancy and one of the men ordered her out of her bedroom, and she pleaded with him ‘not to do anything to her because she was near her confinement. He said, “Never mind”, he caught hold of her, pushed her into the back kitchen, and closed the door.’40 Irish Exile, July 1921 In the kitchen she tore the mask off her assailant’s face ‘and lit a match, to get a look at him, he ordered her to put the match out saying to her, “you are courageous”.’ She said that she fought hard but he ‘succeeded in criminally assaulting and raping me’. 41IbidHe then ordered her to go back to her room, where told he husband about the assault and rape. The couple reported the incident to the police at Shandon.42Ibid

In another report in the same paper there is a story of a young woman who was assaulted by a member of Black and Tans while they were searching her home. She stated that one of the men:

Margaret Connory in her report for the Irish White Cross recorded the emotional trauma experienced by women at the constant personal searches by the Black and Tans, whereby anyone could be stopped on the street and searched. Connory explained that these searches were:

When the Black and Tans began to use female searchers, Connory observed that the situation on the ground was aggravated by the widely held belief within the population that these women were, ‘not such as one would choose to come into close personal contact with’. 45IbidThese women searchers were recruited in England, though it is not clear when this practice started. However, by 1921 the use of female searchers was accepted practice. Margaret Connory was critical of the general lack of female membership on the parish committees of the Irish White Cross, she believed the assaults on women remained unrecorded because ‘men with the best will in the world, were not competent to deal with cases of sexual assaults’. 46IbidShe also suggested that the Irish White Cross should try to avail of the services of the district nurses (Jubilee Nurses) to deal with this issue. However, a point missed by Connory, was that the meetings and the work of the parish committees was voluntary and had to be done in the evenings. Many women were reluctant to leave the relative safety of their homes because it could be misconstrued, by both sides’ and was consequently too dangerous, and is a rational explanation for the lack of women on these committees. The unspoken but palpable terror within the female population had the effect of spreading a profound feeling of dread amongst large numbers of women in the districts where rape and sexual assaults occurred. There is no evidence that Margaret Connery and the elite republican women from Dublin, interviewed any women who were attacked by the republican side. Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, in her pamphlet, had some interesting observations to make about prostitutes. She said that the only women who had freedom of movement after curfew were prostitutes ‘who are presumably seen as a military necessity’.47Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, Statement on Atrocities against Women in Ireland (NLI ILB 300), p 3 She said that in Dublin women were:

However, Sheehy Skeffington did not explain how she knew the difference between innocent women, like the girl attacked by the Black and Tans, and the women she claimed were prostitutes who were also being taken away in the middle of the night in military lorries.

In early 1921, Hanna Sheehy Skeffington organised a deputation from the Irish section of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, to travel in May to the Imperial Conference in London, and ‘present a pamphlet [on the abuse] by distributing it to the individual premiers of the British Empire at the conference’.49RIC police report, documents captured at Glenvar, 22 June 1921 (PRO, CO 904/23), p 5 The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) was an international women’s organisation, which had its headquarters in Geneva. The WILPF was:

Mrs. Dix, and Rosamunde Jacob were the secretaries of its Irish section and the deputation was made up of five members of the Irish section. Sheehy Skeffington approached Michael Collins and asked him for £100 to enable the delegation to travel to London to present a pamphlet to the leaders of the Commonwealth countries who were meeting in London. While Collins and Eamon de Valera did not believe this would be effective propaganda, they were nonetheless willing to give them the money. Collins in a report to de Valera said:

Eamon de Valera concurred with this opinion but decided that because the ‘deputation is composed of the ladies I heard were going, the protest they make will be in every way worthy. If proper publicity is given to their protest, it will have an influence on the women in other countries’.52Ibid 31 Yet in another memo to Art O’Brien in London, de Valera expressed his belief that this protest could only be a publicity stunt. He told O’Brien that if he should see Mrs Sheehy Skeffington, to ‘impress on her the line that she should indicate to the premiers of the various commonwealth countries, that they must share the responsibility for the acts of the British government’.53Ibid.

Soon, national amnesia by republicans, both male and female, reduced the experiences of many Irishwomen to total silence, and were then conveniently ignored. Meanwhile, the elite Republican women, triumphant at their rise within republican politics, remained silent, or were unaware of the ‘war on women’ and the horror to which women’s lives had descended.